Subjective Experience of Ontario Public Education

by Michael Skyba

(Initially written on 2024-07-18)

Preface

A few weeks ago now, I finished my twelfth year of public education, and

graduated from my high school. At last?

I can still picture myself inside the graduation ceremony. The ceiling fans

did little to quell the heat. The graduation gown the board decided on, sold by

a company whose X account I now see has 8 followers, stuck to my increasingly

sweaty wrists. I tried rotating the position of the sleeve every fifteen

minutes, while wondering how much better at negotiating I’d have needed to be to

escape my parent/guardian’s command to attend.

The surrounding seats were filled by students I had never spoken to, and now

hopefully never will. Throughout all of the speeches and presentations, the one

to my left, when not stabbing at the neck of one of his nearby friends in the

next row, scrolled through TikTok on his phone. Another victory for ByteDance’s

training data?

In one section of the ceremony, every graduating student had their name called

sequentially. Each student would walk to the stage, receive a counterfeit piece

of paper symbolizing a diploma, pose for a picture, and then walk off to make

room for the next student. It took at least an hour to iterate through

everybody.

At the start of the section, the announcers clarified that we were to hold our

applause until the very end, but people still opted to clap after each name. The

more popular the student, the more cheering you could hear.

When it was finally my turn, my thoughts turned to the correct procedure for

accepting the paper and shaking the principal’s hand, and my ears failed to make an

evaluation. My guess is that the magnitude of applause would have been in 20th

percentile or so.

A handful of students would yell out inside jokes or otherwise obscene slogans

into the crowd as they saw their friends being called. I wonder how the parents

felt when the principal spoke her grandiose words of praise, emphasizing how

every student in our school would go on to achieve great things. We, the leaders

of the future, comprised the heart of our strong community! I felt sick.

Who was the target audience of this? Is this really what those anime writers

were trying to capture, when they put graduations into their stories?

A subset of the announced awards were for genuine accomplishments, and I clapped

with respect for the recipients. Still, is this what was motivating them to keep

working? Did they feel fulfilled, as they looked around at the restless faces

and held up their prize?

For the finale of the event, it was time for the students to throw their caps

into the air, as a unitive, sacred tradition!

…I couldn’t force myself to do it.

…

Uh… what?

In this post, I will write about some of my experiences throughout schooling.

Perhaps there’s a total of at least three or so people whom could find such

descriptions to be interesting. Mostly, I’m writing this because I expect to

wish to look back on it in the future, and would hope for it to have slightly

more polish than my usual notes.

The focus will be on high school. My memories from elementary school are so

hideous (near-entirely the fruits of my own shortcomings) that I’d prefer to

privately extract the few valuable updates they offered, and toss the rest away.

I only intend to lightly touch on them.

Regardless, these recounts should not be taken as serious evidence for an

assessment of the school board’s quality, considering how overflowingly biased I

am going to be on any relevant topic. I would expect many other students to

disagree on anything I paint as supposedly positive or negative.

Let’s start with the social environment. You can guess that I’m not exactly

qualified to have a strong opinion on it, but I’ll still describe it as

disappointing.

Imagine yourself silently working on your laptop, rubbing your hand across your

hoodie’s sleeve because it’s somehow always freezing in your P3 classroom.

Suddenly, you hear the distant sound of a

crash bar compressing. What do you

expect next?

Hmm, someone must have entered the central passageway through the Great Hall’s

stairwell. They must be returning to class, so I’ll hear them gently close the

door and then calmly walk to their appropriate room.

Ah, what a sweet tale…

…Yeah, that’s not how it goes.

Instead, the first thing you will hear is the sound of the adjacent crash bar,

because the second door is opening, to make room for the stampede of 10 students

who are traveling together.

Huh? What’s that new, high-pitched sound? Did the fire alarm turn on (someone

inevitably has the heroic idea of tripping it as a joke every few months)? Nah,

tuned specifically for you, that’s an original, deluxe mix of screeching and

cackling, because one kid is lunging at the other as the group pushes each other

through the hallway.

Whoa, something’s getting louder? That’s the sound of hard, hurried steps,

because they’re fully sprinting now. That echo of skidding collision, reminding

you of bent plastic? Ah, that’s nothing to worry about. It’s just them literally

tugging the garbage bin off of its hook on the wall and whipping it down the

hallway.

(This is around the point where three different teachers would have to interrupt

their lessons to leave their classrooms and try their best to pacify the crowd.)

Fortunately, the worst of them would skip class entirely and have their

“harmless fun” outside, behind some convenience store somewhere. Also

fortunately, this type of student will often opt to take the “Applied” versions

of courses, making it rare for you to have to handle them directly.

Representative Accommodation

Downstream are some effects on infrastructure, such as the state of the

washrooms. Even in elementary school I had a policy of avoiding public

washrooms, but high school took it to another level.

If you ever come in, even if only to wash your hands, you’ll see a looming

circle of hooded figures, but only barely through the clouds of smoke.

As you reach for the soap, you’ll realize someone has already stolen the entire

dispenser off of the wall, and so you have to use the other side, closer to the

group. You distribute the foam as quickly as you can through your fingers,

hoping to avoid the pieces of gum and mysterious red stains inside the sink, and

then scuttle out of the room, before they have a chance to start offering you

anything. After finally escaping, you’re left with the sense that your hands are

dirtier now than before you entered…

To the detriment of my physical health, I quickly decided to never bring my

water bottle to school, and thus only consume liquid in the subset of the day

after I return home. In certain cases, I’ve needed to make exceptions, and so in

total over my entire high school career, I’ve used the washroom around three

times.

It’s common to hear of other students leaving school at lunch, walking all the

way to the Metro in the nearby plaza

(~5 min each way), using the public washroom there, and then walking back.

Relatedly, almost every school assembly starts and ends with the vice principal

devising new strategies to deter students from their favourite ritual: showing

up late to class, asking the teacher to use the washroom, and then spending the

rest of the period vaping with their friends around the stalls. It never seems

to work, though; it’s still common to see these large groups enter the washroom

together, and thirty minutes later, for an irritated teacher to storm in (“Out!

Now!”).

My guess is that a large minority (~30%?) of students regularly consumed

recreational drugs. My few ~acquaintances were not the type to be interested, so

I lack solid, empirical evidence on this. Yet I have overheard otherwise

seemingly normal people casually admit to, for example, having smoked cannabis

while skipping their previous class.

One student, after learning that my weekends consisted of programming or doing

other work on my laptop alone in my room, genuinely believed I was lying when I

later clarified that I was not relying on any such drugs to support my

lifestyle.

Modafinil? The only drug 🍎 you really need is the upbeat, charismatic

sight of Sam’s smile as he announces GPT-5.

The Zoomer Distribution

Fortunately, many reached the threshold of neutrality, but unfortunately, with

very few exceptions, I didn’t see students who were actively attempting to

acquire knowledge and ability. It seemed like people’s standards only ever

matched, if even, whatever the school, or their parents, directly demanded of

them. The common priority wasn’t anything amusing like deliberately shortening

timelines or Death With Dignity, but instead ensuring an invite to the pool

party being planned for next Friday night.

To clarify, I’m not trying to pretend like I’m particularly noble either. I’d

describe my skill level as a merely pitiful “capable of performing a ‘web

development’ or ‘software engineering’ role at an average tech company”. (Of

course, anybody somewhat capable of learning anything, including me, could be

ramped up into higher roles; it’s hard to draw an exact boundary on cache.)

I believe that this, however, is literally the 100th percentile for my school.

Some students clearly exceed me in certain niches and some were close in total

breadth, but the supermajority didn’t have any care about progressing in

anything.

I suppose you could argue that seeing people avoiding your goals like the plague

gives you a reference for behaviour not to copy. Although perhaps that could

be beneficial to some, it has only ever felt draining to me. External poor

performance only gives me something to point to as an excuse to slack off.

Surely I’ve done enough and deserve a break if I’ve passed N fraction of the

rest? No. I’ve always been and still am far too slow. Subconsciously, it’s a

debilitating

anchor,

in this case for normative self-expectations.

I much prefer the kind of environment where I’m only in, perhaps, the 5th

percentile of ~skill. I’d say this is indeed the case for the circle of Xitter

that I frequent, and although much of my time there has certainly been

counterproductive, it is consistently motivating to behold so many people miles

outside of my figurative reach.

For a long time, I was dead-set on this necessarily being the case in all

possible settings: whenever I would witness any student achieving anything

remotely nontrivial, I would immediately create a long backstory in my head of

how infinitely talented they must be and how much of a living waste of space I

am compared to them. I later came to realize that this isn’t an amazing practice

on an epistemic level, but it still obviously has instrumental value in certain

cases.

For a long time, I was dead-set on this necessarily being the case in all

possible settings: whenever I would witness any student achieving anything

remotely nontrivial, I would immediately create a long backstory in my head of

how infinitely talented they must be and how much of a living waste of space I

am compared to them. I later came to realize that this isn’t an amazing practice

on an epistemic level, but it still obviously has instrumental value in certain

cases.

The staff were usually not too much more impressive. I don’t remember meeting a

single teacher since Grade 1 that seemed to actively pursue further study in

whatever subject they were teaching. (In particularly broad cases, you could say

that gym teachers are “exercising” in their spare time, for instance, but it’s

not the same.)

However, some at least seemed to like their subject, and on the whole, there was

a nonzero level of personal interest in their students learning and succeeding.

A couple were even willing to invest additional time to support students in

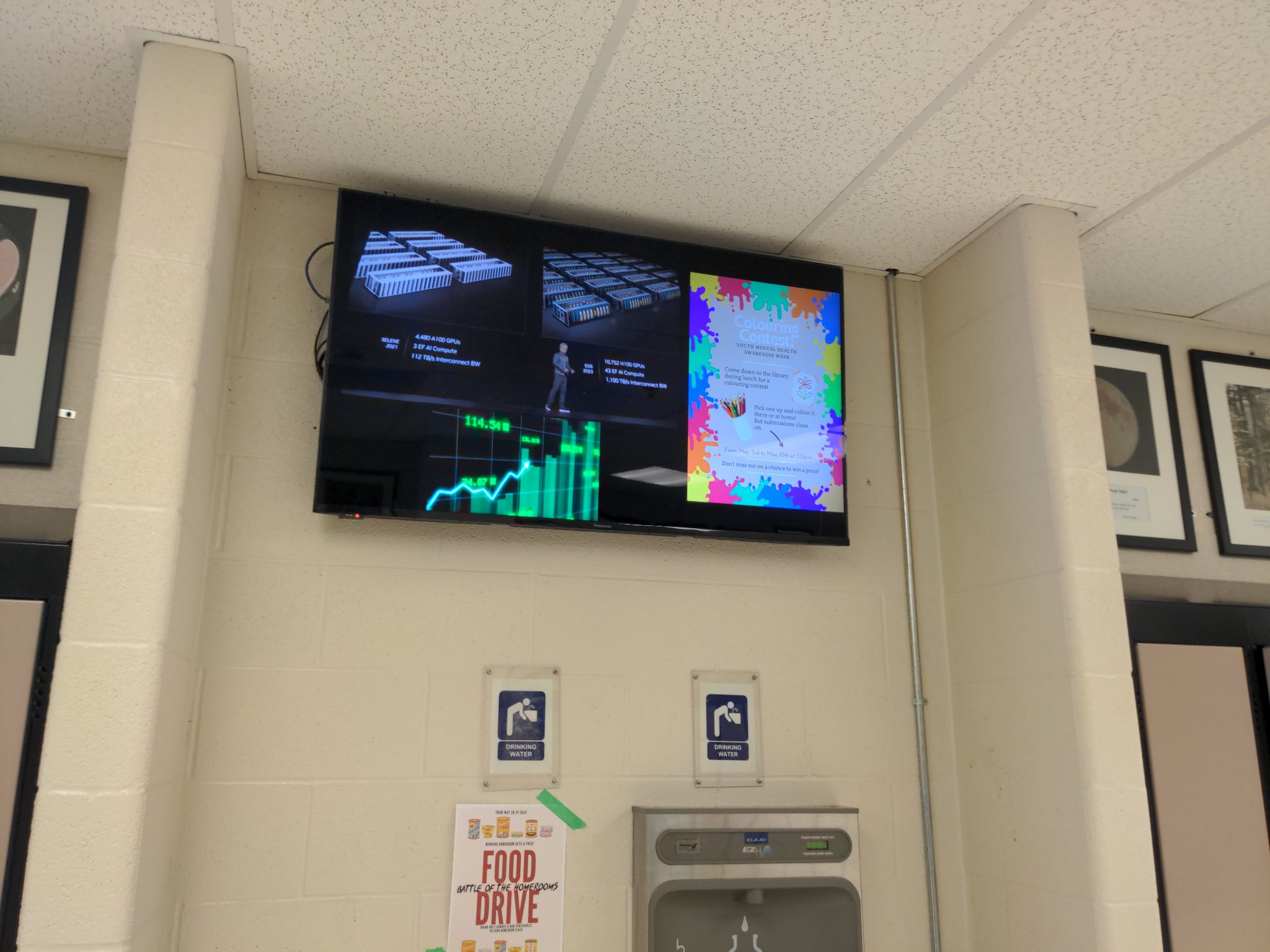

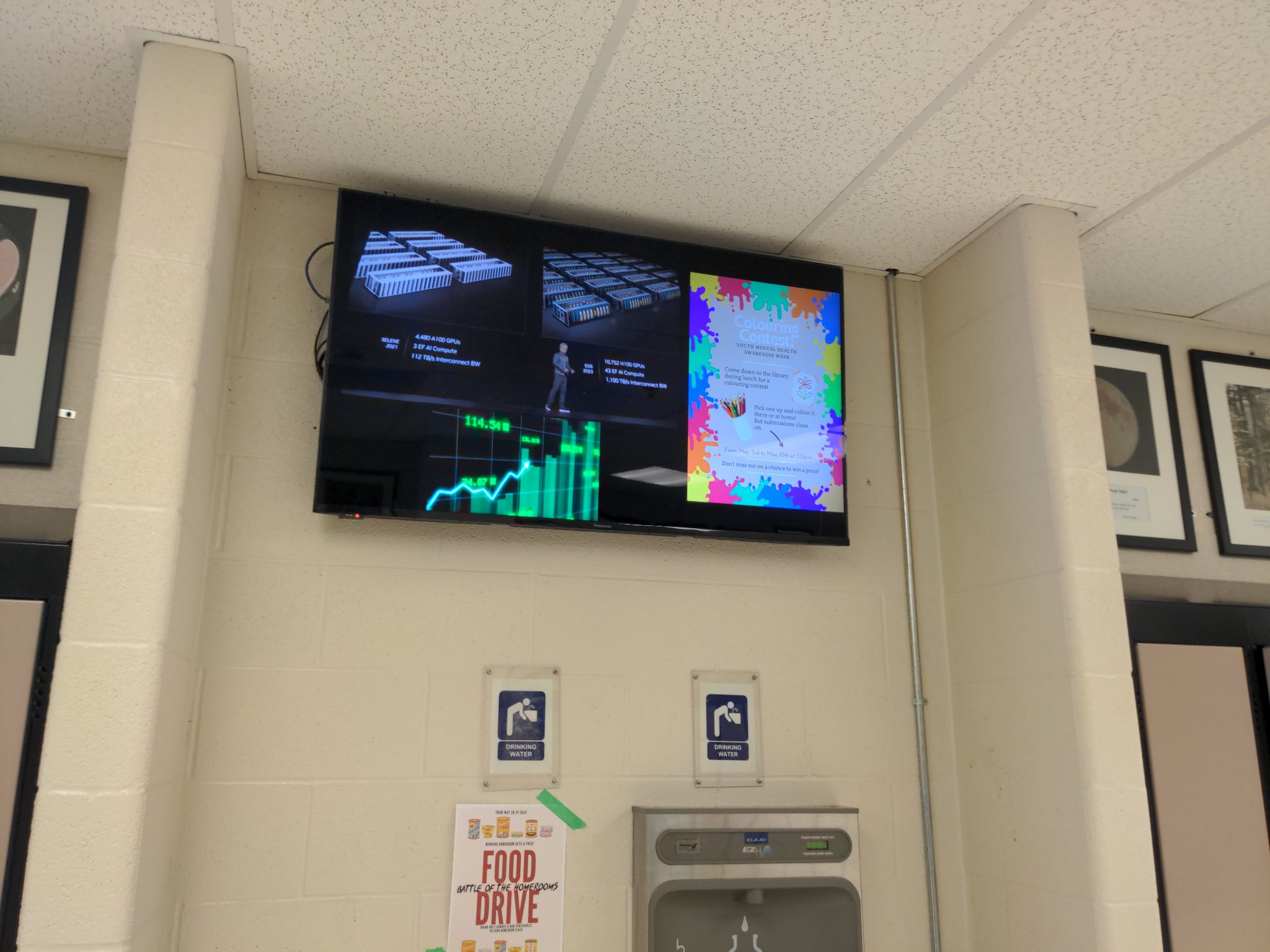

related pursuits outside of class. The CS teacher, for instance, went out of his

way to allocate part of the tech department budget to purchasing Raspberry Pis.

I wrote some software to

run on them, and we ended up deploying them around the TV monitors, as an

additional display of school information.

(The NVIDIA presentation was a test deployment that I soon after had to remove.

For other tests, I played a few of my Advent of Code and Touhou 10 recordings.)

(The NVIDIA presentation was a test deployment that I soon after had to remove.

For other tests, I played a few of my Advent of Code and Touhou 10 recordings.)

I’ve had some other, mostly regrettable social experiences that could be seen as

“interesting”, but I won’t be able to share them publicly.

Quality Content

Sure, anyone can get unlucky with harm by association, but what about the

education itself?

For some context, here is a final screenshot of my user account, on the web

platform the board employs for archiving course marks:

(You can tell that the 100 in ENG4U1 was given by mistake, at least, judging

from the slop of this post so far. I suppose the expectation is for students to

fail even to string simple sentences together.)

(You can tell that the 100 in ENG4U1 was given by mistake, at least, judging

from the slop of this post so far. I suppose the expectation is for students to

fail even to string simple sentences together.)

It makes me feel ill, thinking back on how much time I wasted, how much brain

damage I coerced myself into, all for these tiny numbers. Judging from my

comparisons with other students, the

university programs

I was accepted into would likely have made the same decisions even if my average

was, for instance, 5-10 points lower, which could have saved hundreds of hours.

The picture’s only significance now is that it can lend a few drops of

credibility to my opinion about the processes that determined it. I only know a

handful of students who would consistently earn higher grades than me across our

shared courses.

Coursework

It’d be a safe summary to say that as a whole, my experience with the content of

classes was of dislike. The material suggested by the curriculum to be covered,

while almost exclusively shallow, was occasionally interesting as information.

The bulk of your engagement with a course, however, is not the lessons. It’s…

the homework assignments…

Since Grade 1, I don’t remember hearing a single student ever unironically

express fun or enjoyment at work they’ve been given to complete. I can’t speak

on their behalf for what they value spending time on, but in my case, a large

component of the drag was that the instructed tasks would be laughably

inefficient ways to become familiar with the relevant topic.

Even if the content itself was something I was genuinely interested in,

I was left with a constant sense that anything I was doing was not for my own

benefit, but to satisfy a teacher running out of ideas on how to “creatively”

design an activity.

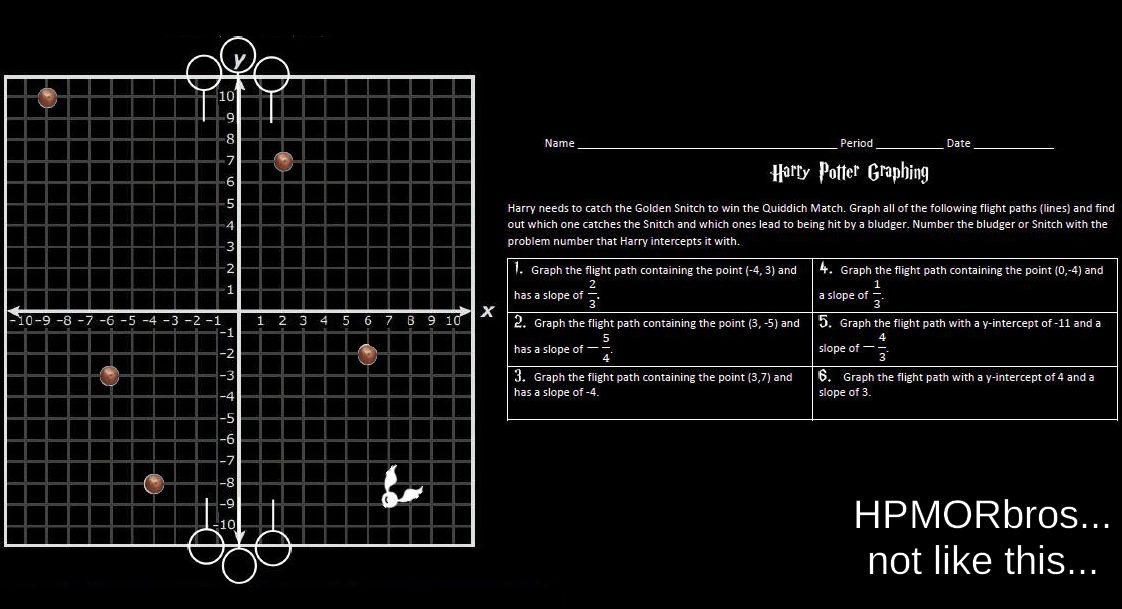

As a minor example, part of the

defined curriculum

for Grade 9 MPM1D1 is that students should grasp the basics of linear relations

and analytic geometry. If the course was designed with so much as a grain of

respect for the student, a relevant task might involve thinking through

something like the following:

- a) Given a real number r between 0 and 1 and two points P = (x1, y1)

and Q = (x2, y2) in the plane, find the coordinates in terms of r of the

point T on segment PQ such that PT/PQ = r.

- b) What happens if you allow r to be greater than 1 in your formula in

part (a)? Where on the line connecting P and Q is the resulting T?

- c) What happens if you allow r to be negative in your formula in part (a)?

Where on the line connecting P and Q is the resulting T?

(This is problem 8.59 from

AoPS Intro to Algebra.)

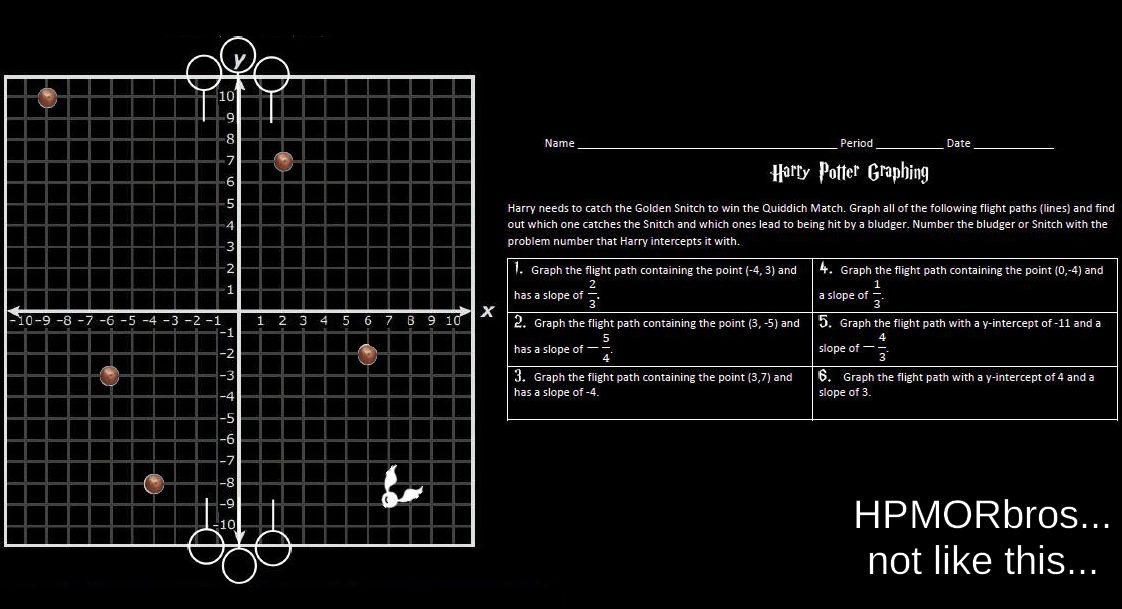

Instead, in an actual MPM1D1 course, a breathing adult will look at you with a

straight face as they toss you leftover vomit:

(This exact image is only of a worksheet; a marked, summative assignment in

MPM1D1 would be similar except with 10x more of the same questions, and no

option to submit work digitally.)

(This exact image is only of a worksheet; a marked, summative assignment in

MPM1D1 would be similar except with 10x more of the same questions, and no

option to submit work digitally.)

Vaporous whispers spoken by ghouls, encouraging head-bashing

Mathematics makes for a clear comparison, but in this respect, the most

subjectively wearisome assignments would often come from humanities courses.

They would demand a large amount of thought about and effort into something

backwards and inconsequential, mostly unrelated to the actual course subject.

Depending on the severity, it’s common to hear other students complain about the

magnitude of work, or a feeble “sigh …Why do we have to do this?” You can

witness the looming discomfort usually convert to them ducking under their desk

and opening Snapchat.

For most students, I think this is a natural form of

Yudkowskian

procrastination.

When actually engaged in the work, they have, at most, a mild frown on their

faces.

For me, I don’t think this standard model fully applies. As an analogy to my

perspective, imagine sitting in front of a small button. Though its glossy

surface may appear innocent, if pushed, an activated mechanism will proceed

to slowly cut your entire left arm into little slices of meat and bone. Staring

at the button, the inevitably induced procrastination may leave you compulsively

squirming in your seat.

In this scenario, the pain in procrastinating is not out of shame at yourself

for not having started, but out of genuine fear. The inherent cost in switching

tasks itself is trivial, and any temporal discounting will be of the future pain

of your entire body going through the same chopping process (the theoretical

price if you ultimately fail to press the button at all).

I’m only moderately exaggerating. The same functional dynamic would apply

to my experience with many such assignments. Every minute spent working on them

would feel like being not simply annoyed but actively injured, with each

internal scream of "Please… please stop" only delaying its end.

In exceptional cases, I was simply incapable of forcing myself to flood the

searing pain through the entirety of my conscious attention. Despite the

accompanying nosedive in productivity per unit of time, I’d need to primarily

focus on a neutral, unrelated activity, and only occasionally jot another idea

or line down on the course task in the background.

The harshest such assignment was definitely the culminating of Grade 11 English.

By itself, it would already have been nearly unbearable, but it also compounded

with some severe, external issues I happened to be managing at the time. I don’t

know if I could have pulled through if I wasn’t rhythmically chanting to myself

all throughout:

Based on my current academic, professional, and personal trajectory, it is

highly probable that the pain inflicted on me in this moment will have been the

most excruciating out of the entire duration of my lifetime. If I can somehow

survive these next few days, it’ll all be downhill from here…

(For a number of reasons, I’m not going to describe the actual work involved in

the culminating.)

Perhaps in part related to these assignments is that over time, a growing

fraction of my habits, routines and overall mental infrastructure have developed

solely around this meta problem of “coping with dissatisfaction”.

A Violent Love: Material and Distortion

Fortunately, unlike summative assignments, in-class informational lessons are

easy to ignore. I started doing so the second I had the maturity to assign a

hint of thought to what I was spending my time on. It quickly became apparent

that even if I made my best effort to pay attention, I wasn’t going to be

learning much of anything.

One fairly early example is that during Grade 10 GLC2O1, we students were

supposed to be learning about personal finance, so in class, the teacher (“H”)

showed us sample, hypothetical student budgets. In these budgets, a small

fraction (e.g. 10%) of your income was allotted to a “savings” bucket, and then

you would actively and deliberately seek out random expenses to fill the

remaining 90%.

I was fully expecting to hear a lecture on why this is a terrible plan to

follow, but H instead described it as perfectly reasonable, going so far as to

affirm that 10% was atypically high. Upon witnessing this, I was deeply

disturbed. A rare sense of gratitude appeared towards my past self for at least

having learned about relevant basic concepts like the compound growth of market

indexes.

After class, thinking that I must have misunderstood something, I asked H why

the examples weren’t trying to minimize expenses and reach, for instance, an

80% saving rate, rather than a 10%. H’s response was that lower spending

is conceivable in theory but will involve far too much willpower than what can

be implemented in practice. I was told that over the course of my future career

(implied: many decades), 10% is already sufficient for eventual retirement.

(At the time, I had already decided to skip common memes like going out to eat

during lunch or purchasing Clash Royale gems. My only expenses were of buying a

Touhou or Danganronpa game once every six months: without being particularly

diligent of a student or a person, my rate was around 95%.)

This pattern repeatedly applied across any topic covered that I felt even

somewhat comfortable with my prior understanding of. It wasn’t limited to

disagreements in philosophical stances: I often heard teachers explaining

ideas in ways that were inconsistent and self-contradictory. They assumed you

were incapable of following the standard theory, and thus would rely on leaky,

oversimplified analogies that discarded critical nuances in the original

concept.

I’m left to assume that in courses whose content was entirely new to me (e.g.

Physics), a more knowledgeable third party would similarly be unimpressed with

the presentation.

Most students, of course, only care about extracting the

password

that will later need to be regurgitated on the test, in which case any mutually

perpetuated errors aren’t a particular issue. The few who have genuine interests

in deeply grasping the material, however, will essentially have to start from

scratch and relearn everything on their own.

Expensive Responsibility

The final notable component of your experience as a student will be the iron

insistence with which teachers enforce their personal intuitions about optimal

learning and work systems onto you.

As an example of what this can apply to, being physically within the walls of

the school has always felt threatening to me, regardless of where I was. Some

sense of composure and subjective “safety” is important for me to focus, so this

spatial discomfort was an added layer of resistance I had to endure when

completing the already draining assignments.

Hence, it was always most efficient for me to leave the particularly painful

work for when I arrive home and have more control over my environment, in my

room. During school hours, I preferred to complete tasks that were either

cognitively light, like reading through entries in my RSS feeds, or

intrinsically motivating, like

solving K&R exercises.

Teachers, of course, have zero sympathy for such approaches: when you’re

physically present for the specified 75 minutes of class, they demand that you

also be mentally present for 75 minutes.

A common variation of this I’ve noticed in other students is that they sometimes

have an important assessment scheduled for their next period. If we’re not

engaged in anything particularly urgent, a student may wish, quite reasonably,

to neglect whichever frivolous time sink we were handed, and instead spend the

current period studying. You can guess what a teacher’s reaction to this is if

they learn of it.

Among myself and many others, the result is not a magical loyalty to the

teacher’s whim. I continued trying my best to optimize my schedule, to

work on what I most believed in at the moment. Yet within this state, much of my

mental effort had to be spent maintaining a dynamic mental model of the position

of my seat relative to other entities in the classroom. I needed to be ready to

switch the active desktop of my laptop’s window manager, depending on the

teacher’s viewing angle.

Such practices were as greatly irritating as they were distracting.

Occasionally, teachers enjoyed wandering the room so relentlessly that I had no

choice but to work as they intended. Every time this happened, as expected, my

pace of progress was a crawl compared to when I’m at home. I was initially

reluctant to disobey official instructions in Grade 9, but I gradually

discovered that faithfully pursuing my goals was incompatible with external

honesty.

A more asynchronous example of this is that in mathematics courses, teachers

assign pages of mindless homework and genuinely expect you to complete every

exercise. (These were similar in style to the graphing worksheet I displayed

earlier, but would be designed to consume around 45 minutes of your spare time

per day.) In four out of five of my math courses, teachers regularly performed

“homework checks”, sequentially visiting each student to confirm that your

notebook contained solutions, while marking down notes on a list of names.

Halfway through Grade 9 MPM1D1, I became aware that these checks only influence

the “Learning Skills” section of my report card and not my actual grades.

Shocked, I asked the teacher whether there was any other possible motivator for

students to heed them. After receiving a blurry answer about how I couldn’t

possibly be expected to comprehend the material otherwise, I stopped all

homework, and haven’t completed a single question since.

I understand that for certain students, this sort of micromanagement is entirely

necessary, but there is literally nobody to whom they are willing to extend

trust. If a student has a 100.0% in your course, maybe they know a thing or

two about effective work and study habits? Perhaps at least consider treating

them as something close to an autonomous agent?

Grade 12 MCV4U1 was an outlier: the teacher seemed to realize that my time was

being wasted by the forced in-class practice questions at the white boards, and

then chose to exclude me from the student pool when randomly compiling work

groups. From that point onwards, each day, I would simply show up to class, sit

with my back bent on the awkwardly-shaped bar stools, and type away on my

laptop.

For that one course, I was completely free to handle my own studying for

examinations, to not have any pretense of care for whichever mockery was being

discussed in class. (Most lessons would involve extensively describing an

algorithm to solve a supposedly new “special case” of a problem type. Anybody

should have been able to derive the steps independently within a few minutes of

thinking, but no, something apparently justified spending weeks on them.)

My resultant lack of class participation resulted in an S (“Satisfactory”; the

second-worst evaluation) for “Collaboration” on my report card.

Was it worth it? Heavens, no, but…

These twelve years had nothing close to a positive ROI on their own terms, but a

nontrivial silver lining exists. Any somewhat valuable knowledge or ability I

currently possess has developed downstream of the following chain of

realizations:

- I have XYZ goals regarding which skills I wish to acquire.

- The default “education” thrust on me is entirely irrelevant or even

counterproductive to XYZ.

- Therefore, the only way to escape mental destitution is to make a deliberate

effort to control my time and figure out XYZ on my own.

If the school’s quality was a mere 20% higher, if a few teachers were

just slightly more willing to engage with my clarification questions… then

maybe #1 would have stayed diluted, I would never have been conscious of #2, and

everything would have went wrong. Perhaps I would still be peacefully gliding to

university right now, rather than bitterly complaining inside a markdown file.

(Being glad that a process accidentally changed your utility function is a

highly questionable form of praise…)

In hindsight, George Hotz’s yearbook quote is remarkably wise:

“If something’s worth doing, then it’s worth doing well. Most things are just

not worth doing.” (paraphrased)

If I had to relive school again, I’d make the absolute minimum time investment

required for a 50.0% average (barely earning every course credit) and then

muster as much focus as I can into other, actually useful pursuits.

(Besides the parental pressure, a barrier to such an approach is the increased

difficulty of self-assessment: “Sure, I tell myself that I’m strategically

underperforming on these narrow tasks, but could I really have done any better

if I tried? Am I just incapable of anything?” I suppose in this respect,

projects like

AoC 2015-19-2 have been far more

directly cognitively demanding than any school assignment, and therefore can

provide a better reference.)

My only experience with private education was in a Russian-language

Montessori program that I

attended, from ages ~4-6, instead of the junior and senior kindergarten years

that public elementary schools offer. Judging from my memories of it, the

competence of the single teacher, paired with the smaller class size of 5-10

students, resolved almost every issue I’ve described, although I’m not sure how

well it would scale to higher years.

There are a few other scraps of use that high school has produced, such as my

newly diminished fear of “work” in general: I now have little expectation that

anything will come close in discomfort to experiences like the Grade 11 English

culminating.

However, it’s also evident that I would have been many years ahead of my current

self by now if my time was being used even somewhat optimally. Simply spending

all those hours talking to GPT-4 about the topics in the curriculum, for

example, would already be a massive improvement over dying inside a classroom.

I’m bullish on similarly self-paced alternatives to the traditional environment,

such as

AoPS,

Math Academy, and Andrej’s upcoming

Eureka Labs.

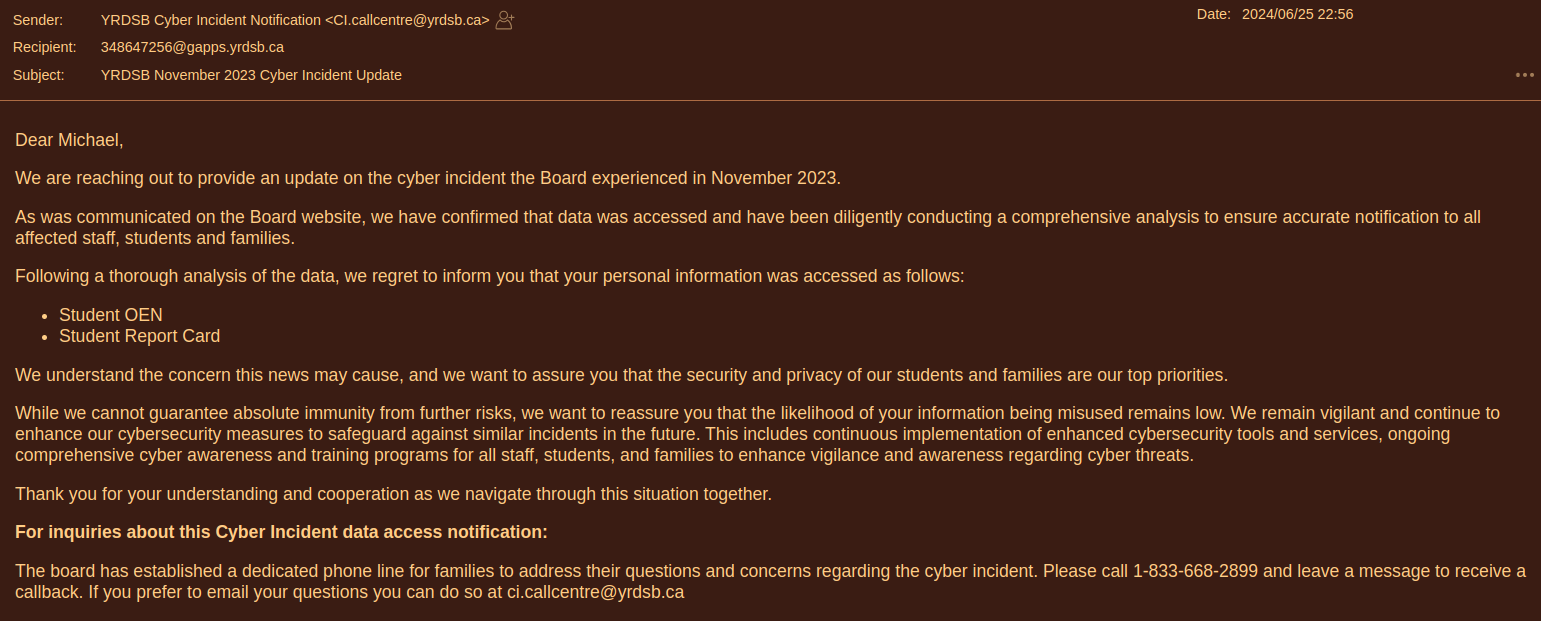

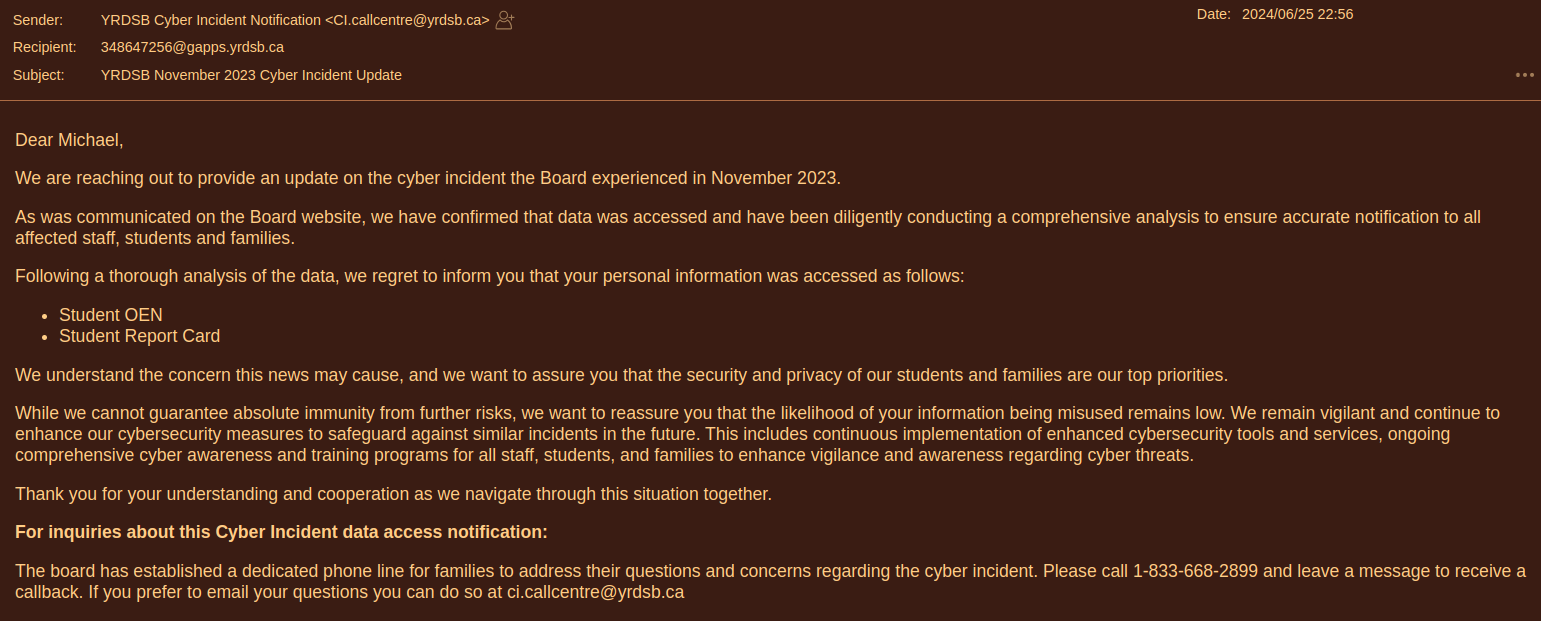

As a final summary of my school board, here’s a real email I received near the

end of Grade 12, regarding a supposed cyber attack that crashed the school’s

attendance tracking infrastructure for a few weeks in 2023:

Oh no! The scary hacker entered the default password on a public route that the

server admins didn’t bother to configure! My, how lucky we are to have the brave

and “diligent” YRDSB to protect us…

Anything next? Apart from more slop?

In the couple of weeks since graduating, I’ve gained something roughly adjacent

to work experience. I can now attest to the fact that adding bells and whistles

to the web application of a generic media service does not feel intrinsically

valuable.

One moral is that your work circumstances are a reflection of yourself and that

I’m in a situation of trading time in exchange for nothing because I’m stupid. I

happen to have some amazingly convenient excuses related to my family and living

situation, but still, it’s true that I need to be planning more carefully and

working much harder.

In a reasonable setting, you’d at least divert your direct monkeytyping time

into dev infrastructure time, setting up more efficient feedback loops with

LLMs. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work particularly well when it takes two weeks

for the company to approve your installation of Git, and only after wrestling

with three different security officers whose job it is to protect the stock

price from you.

In contrast, the small bit of work I’ve done for

OpenAI’s bug bounty program, while frustrating in

certain social aspects, felt meaningful enough to greatly spike my standards.

I’ve grown annoyed with anything whose only return is sustaining basic needs for

survival, or even worse, generic “career advancement”.

It’s hard to predict the short-term impact of AGI, so I’m not sure to what

extent any life decisions that are presently regarded as serious are going to be

mattering soon, though.

I don’t expect any solving of the alignment problem (sorry, Mira, but my strict

policy is to copy-paste Eliezer’s

conclusion without

reading a word of the theory). Regardless, in a supposedly successful post-ASI

world, these issues may make even less of a difference. I’m not sure how anyone

is going to pretend to extract meaning from their original status or trait T=1.5

being higher than the average T=0.9, once everyone (except Zy) has already

self-augmented into T=1000.

…

Article Index For a long time, I was dead-set on this necessarily being the case in all

possible settings: whenever I would witness any student achieving anything

remotely nontrivial, I would immediately create a long backstory in my head of

how infinitely talented they must be and how much of a living waste of space I

am compared to them. I later came to realize that this isn’t an amazing practice

on an epistemic level, but it still obviously has instrumental value in certain

cases.

For a long time, I was dead-set on this necessarily being the case in all

possible settings: whenever I would witness any student achieving anything

remotely nontrivial, I would immediately create a long backstory in my head of

how infinitely talented they must be and how much of a living waste of space I

am compared to them. I later came to realize that this isn’t an amazing practice

on an epistemic level, but it still obviously has instrumental value in certain

cases. (The NVIDIA presentation was a test deployment that I soon after had to remove.

For other tests, I played a few of my Advent of Code and Touhou 10 recordings.)

(The NVIDIA presentation was a test deployment that I soon after had to remove.

For other tests, I played a few of my Advent of Code and Touhou 10 recordings.) (You can tell that the 100 in ENG4U1 was given by mistake, at least, judging

from the slop of this post so far. I suppose the expectation is for students to

fail even to string simple sentences together.)

(You can tell that the 100 in ENG4U1 was given by mistake, at least, judging

from the slop of this post so far. I suppose the expectation is for students to

fail even to string simple sentences together.) (This exact image is only of a worksheet; a marked, summative assignment in

MPM1D1 would be similar except with 10x more of the same questions, and no

option to submit work digitally.)

(This exact image is only of a worksheet; a marked, summative assignment in

MPM1D1 would be similar except with 10x more of the same questions, and no

option to submit work digitally.)